Susanne Hablützel breaks up her work day by staring out the window at a rooftop garden. The view is not spectacular: a pile of dead wood sits atop an untidy plot that houses chicory, toadflax, thistle and moss.

But Hablützel, a biologist in charge of nature projects in Basel, is enthralled by the plants and creatures the roof has brought in. “Tree fungi have settled in the trunks, and they are great to see – I love mushrooms. You can also see birds now – that wasn’t the case before.”

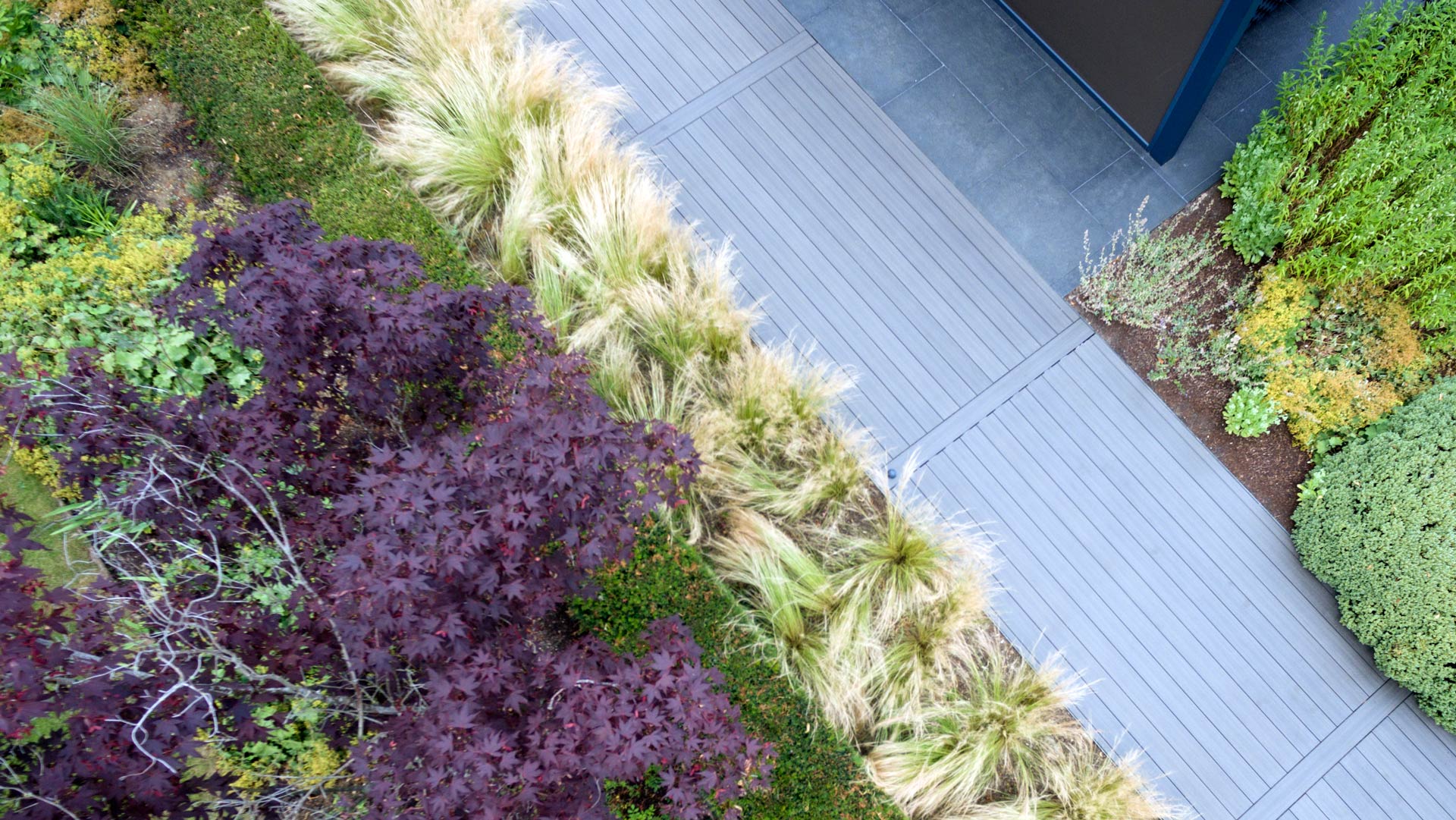

Hidden high above the streets of Basel is an unappreciated environmental wonder: thousands of gardens perched on otherwise unused roofs. As a result of policies set decades ago, the city boasts some of the greenest rooftops in Europe – averaging more than five square metres (50 sq ft) per person in 2019, or about the size of a large balcony.

The roofs range from those on small office buildings, such as the one on which Hablützel spies blackbirds snapping worms into their beaks, to the vast open spaces that cover shopping malls, warehouses and hospitals. But what makes Basel stand out from many other cities that have pioneered green roofs, industry insiders say, is that it has insisted on using native seeds and plants – and not treated green roofs as a box-ticking exercise.

“The green roofs in Basel were like industrial wastelands, which have really good wild flowers,” says Dusty Gedge, president of the European Federation of Green Roofs and Walls, who visited the city in 2000 and brought its ideas back to London. He describes Basel’s roofs as being like brownfield sites that are closer to dry and nature-rich grasslands than monotonous green meadows.

“Now, you show that to most people and they go: ‘I don’t want that on my roof,’” says Gedge. “But that’s what delivers for biodiversity.”

To view the full article, please click here.